In the Beginning:

Mentorship at the Women’s Technology Empowerment Centre (W.TEC)

I started working in the “gender and tech space” (if you can imagine that such a space exists) in 2001. For a few years before that, especially once I started my Masters programme in Information Systems, I had been aware of the lack of women using and working with technology.

As I pored through the literature, appalled by the low representation of women, I became determined to “do something” about it.

I started from my very first formal job, which was in a research capacity within a nonprofit organisation in the United States, looking at how men and women were using the Internet for online learning.

We drew from the large body of research that was already available on the topic, while our project also contributed more data to this body of knowledge.

When I moved to Nigeria, intent on creating similar interventions, I first had to deal with a lack of awareness about what the gender gap in technology was. There appeared to be no sense that there were few women accessing and using technology in meaningful ways. That there were relatively few women working in and with technology was not recognised. There was very little in the way of research to back these observations up. So, where the problem was recognised, it was treated with very little seriousness.

Understanding the Problem:

Thankfully, there is a greater awareness now of the under-representation of women in technology and the wider STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) disciplines. This could be partly as a result of the efforts of the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) declaring the fourth Thursday of every April as International Girls in ICT Day. With the resources and reach of this international UN agency, already available research was distilled into easily-digestible packets, which national governments, ministries and departments of education, women-focused organisations, nonprofits, schools and other interested members of the public were encouraged to share. And so began a more coordinated global awareness-raising effort that reached the most diverse audience yet.

Where there had existed a few decades worth of research on the “digital divide” especially about the gender-related dimensions of this divide by academics and practitioners (Unlocking the Clubhouse: Women in Computing by Jane Margolis and Allan Fisher, published in 2001, is one of the earlier seminal books on the topic), my strong sense was one of the authors “preaching to the choir.” The people who read these reports – like myself – were already somewhat aware of and interested in doing something about this gap.

When I spoke to industry professionals, the media and government officials about getting more women in technology, the responses were not very encouraging and showed a lack of awareness about the existence and depth of the problem or complete disinterest.

– “So women are not working in technology? But I know one woman who does xyz ….[insert role here]….”

– “So what?”

– “Maybe women aren’t interested in working in technology.”

– “Why force women to do something they are obviously not interested in?”

– “So what?”

– “If women are not there, it’s because they don’t want to be.”

– “Women don’t have the kind of disposition for technology and science.”

– “The work is hard. Women are too soft and gentle to handle it.”

– “So what?”

When corporations started funding studies to examine the state of women in the workplace and highlighted the importance of increased gender diversity, this perhaps made the strongest case, because the reports demonstrated identified a positive correlation between more women in leadership and the financial bottom-line. And as they say, “money talks.”

The 2007 McKinsey & Company’s Women Matter Report observed, based on its research, that “companies with a higher proportion of women on their management committees are also the companies that have the best performance.” While it also recognised that its studies demonstrated a correlation and not necessarily a causal link, this snapshot still showed that gender diversity was a good thing for companies.

When I founded the Women’s Technology Empowerment Centre (W.TEC) in 2008, I did not know of more than two other Nigerian organisations focused on attracting and retaining more women into technology.

In 2019, when TechCabal started to map Nigerian initiatives working to get girls and women into technology, it listed more than 30.

Now in 2021, there are far more than I can count. The more, the merrier, I say. We need all the efforts we can, particularly well-thought out and implemented initiatives.

I hear some people say: The problem is not attracting girls to technology, it’s keeping women in technology.

Others say: Girl-focused programmes are inherently sexist and replicate all that is wrong with the system.

Some ask: What about the boys? They will get left behind.

And still others opine: Small initiatives that target 10 or 20 girls won’t move the needle. You need huge efforts that scale to millions.

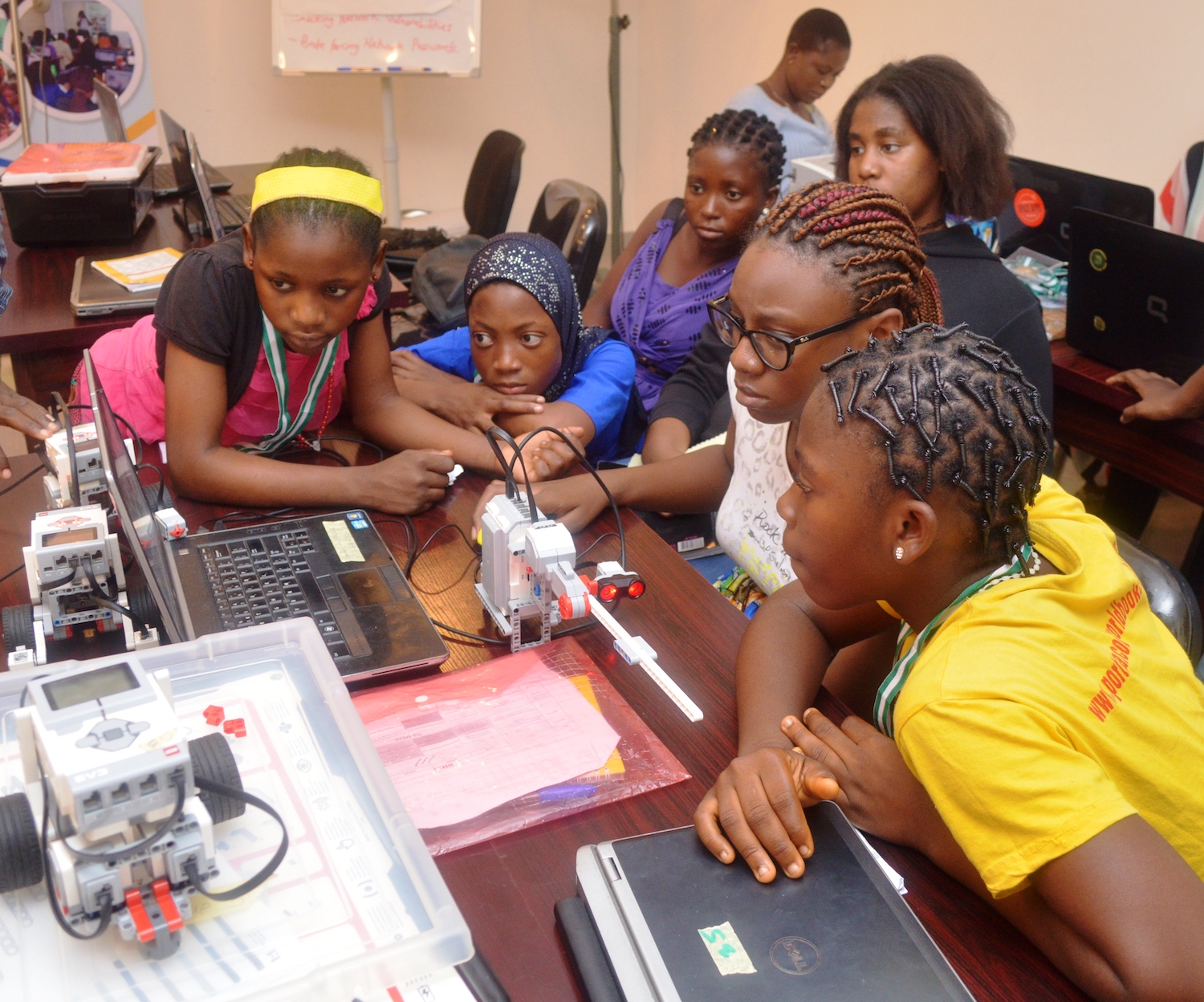

Girls at the W.TEC She Creates Camp

So What Next?

I can’t claim to have all the answers, but my thoughts are that:

1.) The road to parity in technology is long and requires a multi-level and layered approach: This necessitates addressing it from different points. It is important to inspire girls to want to learn more about technology and even pursue related careers. We know that up to about the ages of 12 or 13, girls are as interested in science and technology as boys are, but as adolescence hits and the subliminal messages of who fits in the STEM world starts to sink in, many girls start to lose interest. And this is why, programmes targeted at sustaining girls’ interest is crucial. These could be mixed-gender initiatives, but in these settings, it is important to thoughtfully design the programme so that girls are able to express themselves comfortably and not have to compete with the boys for the opportunity to talk in class or use the computers or other equipment being used to teach. The facilitators must be mindful to call on girls as much as the boys.

2.) You still can’t be what you can’t see: This is a well-cited saying to the point of cliché for a reason. It has a lot of truth in it. It is not impossible for girls to aspire to be an astronaut even if they don’t personally know one. However, it is easier to connect a dream to a reality by developing a roadmap when she has some guidance and encouragement. Therefore, there is a lot of value in mentorship programmes and those that showcase role models, because they give life to dreams and demonstrate what is possible.

3.) Data is Gold: In Nigeria and on the African continent, data and statistics on the breadth and depth of the gender disparity in technology and STEM is still hard to come by. Data, where available tends to be drawn from smaller sample studies or the compilation of secondary data sources. More organisations need to invest in research, because accurate and rigorously-sourced data provides context and understanding of the nature of the under-representation and gives pointers to potentially effective interventions (the TechCabal 2020 Nigerian Women in Tech report is a good one). However, good research can be expensive, require specialised skills and takes years to complete, so it’s easy to understand why more organisations don’t engage in it.

W.TEC completed the IDRC-funded Radio for Women’s Development: Examining the Relationship between Access and Impact research project. And although this was a fairly smaller-sample project (with 200 subjects), it took about four years to complete from the proposal stage to the publication of the final case study article. However, the benefits of good-quality research was evident pretty quickly, as the findings informed, among others, the setting-up of Nigeria’s first women-focused radio station – W FM 91.7.

W.TEC continues to invest in producing factsheets and infographics about the gender gap in Nigeria.

4.) 1 + 1 = 11 aka Build a total pipeline that educates and prepares girls and women for working in STEM: As I already asserted, there are multiple ways to correct the under-representation of women in technology and no way is better than the other (in my view). It’s as important to work with girls in primary and secondary school as it is to mentor young female technology professionals as it is to ensure that female entrepreneurs have access to funding and other support needed to grow their businesses. Since there is immense value in focusing and building a niche, it is crucial that there are organisations working at different points of the value chain, who can complement the others’ efforts.

Organisations like W.TEC work at the earlier stage of the pipeline and we are happy to know that when our work is done, there are other initiatives that will support our beneficiaries as they move on to the next stage of their educational and professional journey.

The Noble Prize-winning physicist and chemist, Marie Curie said that, “I was taught that the way of progress was neither swift nor easy.” Much can be said about the road to parity, but with the persistent and collective efforts of the organisations and initiatives working in this space, supportive government agencies, educational institutions and everyone who cares to see more girls and women confidently using, building and creating value with technology, we can start to create a more level, open and welcoming ecosystem.

Recent Comments